China is building a data privacy framework inspired by the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)

This year has been a turning point for data privacy in China. Internet majors Alibaba and Baidu faced lawsuits and official warnings over data privacy violations. The government has begun enforcing stricter privacy rules and new rules lay the groundwork for a privacy regime that will protect citizens from privacy encroachments and misuse of their data by companies.

What next

Recent and forthcoming regulations will in theory make China a global leader in data privacy. However, enforcement will be hampered by widespread corruption and weak supervision power of governmental agencies. The new framework aims to protect Chinese citizens from corporate misuse of their personal information, but will not protect them from government surveillance.

Subsidiary Impacts

- The similarities between the Chinese and EU frameworks will facilitate economic exchanges.

- The new rules may create difficulties for US or Australian firms in China, which lack a comprehensive privacy regulatory framework

- Relaxing policies on encryption will level the playing field for foreign encryption companies in China.

Analysis

A thriving illegal data market has appeared in China that allows individuals and companies to buy personal information very cheaply. In a China Consumers Association survey this year, 85% of respondents reported being affected by data leaks, ranging from theft of banking information to phone and email scams.

Public awareness of privacy issues is growing

More than 70% of respondents to a 2016 survey said that personal information leakage was a serious problem. Baidu CEO Robin Li said in April that China’s public was willing to trade privacy for convenience. A popular backlash disproved this.

Privacy push

The government has developed regulations to address these concerns. Amendments to the Criminal Law in 2015 extended criminal sanctions to individuals (instead of just government departments) for selling personal information.

This opened the way for regulations protecting private data, mostly since the Cybersecurity Law took effect in June 2017. That law lays out fundamental principles of “personal information and important data protection system”.

The Personal Information Security Specification took effect in May this year. It is not legally binding but provides detailed guidelines for the collection, processing, storage and sharing of user data, which will be used by regulatory agencies to implement the Cybersecurity Law. Several draft guidelines on cross- border transfer of personal data are in the pipeline.

Documents issued in September and October also remove requirements that companies seek approval for the production, distribution and use of encryption products.

More guidelines will likely be issued in early 2019, and three important laws are on the legislative agenda: the Data Security Law, Personal Information Protection Law and Encryption Law. These feature in the five-year legislative plan of the 13th National People’s Congress Standing Committee, released in September.

Details of the framework

The legal framework now laid out is almost identical in scope and approach to the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR):

- Personal data are defined as any data which, on their own or combined with other information, identify a natural person.

- Companies that collect personal data must disclose to the user what information they collect and how it will be used. They must keep the data no longer than needed to achieve the stated purpose.

- Companies must obtain explicit user consent for collecting and sharing the data, and for each purpose of data processing. They must conduct a security assessment before selling data to a third party.

- Companies must erase or anonymise personal data within 30 days when users close their accounts. Users have the right to erase their data if the company breaches its legal obligations.

- Users can appeal if companies use their personal data to make automated decisions that could harm them (such as profiling, credit rating and screenings of job applicants).

- “Critical information infrastructure operators” in key industries, such as information services, finance, energy, or public services, must store data within Chinese territory.

There are minor differences from GDPR:

- Exceptions from the consent requirements and from compulsory notification of security breaches are more limited in the Chinese framework.

- The Chinese framework includes broader requirements for compulsory appointment and training of data protection staff.

- The Chinese framework includes stricter penalties, which range from maximum fines of 1 million renminbi (145,000 dollars) to imprisonment; GDPR has fines alone.

Implementation

Even as the detailed privacy guidelines were being drafted, the government started requiring companies to revise their privacy policies.

In January, the government reprimanded three large internet companies over data privacy violations – Baidu, Ant Financial (the payments subsidiary of Alibaba) and Bytedance Technology (owner of popular news app Toutiao).

Highly publicised cases this year show that the government is serious about enforcing data privacy rules

The same month the Jiangsu Consumer Council, a government-backed consumer protection association, sued Baidu for collecting user data without consent. The Council also reviewed the privacy policies of 27 mobile app operators and forced most of them to change their privacy policies. Also in January, the National Internet Information Office Cyber Security Coordination Bureau required Ant Financial to review the privacy policy of its payment service, Alipay, after the app’s default opt-in features signed users up for the app’s credit rating programme, Sesame Credit, without their consent.

The emerging data privacy regime will take several years to complete

Government usage of data

While the European data protection framework explicitly exempts public authorities acting in the public interest from obtaining user consent, the Chinese framework does not distinguish clearly between corporate and public actors. However, it states that “complying with the mandatory requirements of the competent government authorities” is a legitimate legal ground for sharing personal information. This allows government collection and processing of data.

Beijing is also facilitating the collection of personal information for law enforcement and public decision-making. In particular, the Cybersecurity Law requires companies to verify users' real identities. The Cybersecurity Law also requires companies to store customer metadata (time and location of phone calls, text messages, emails and internet activity) for at least six months. This data can be accessed by the government for law enforcement purposes.

The retention of metadata by companies is also compulsory in Australia for at least two years, and in the United Kingdom for at least one year, so China’s rules are actually less heavy-handed in comparison. Moreover, Australia recently passed a law allowing public authorities to demand that companies provide the content of private messaging, even if that means weakening their encryption system. However, there is no doubt that the Chinese authorities use their powers in ways Australian authorities do not.

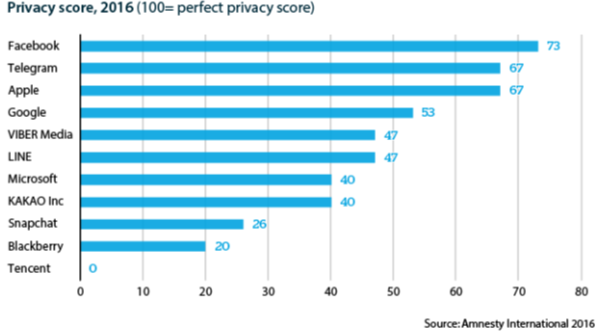

Weak encryption also facilitates mass surveillance in China. WeChat ranked last in a 2016 Amnesty International report on the effectiveness of encryption in eleven global messaging apps. Chinese authorities are known to use the content of private online messages to incriminate individuals and curb freedom of speech.

The Chinese government’s project to build a social credit system by 2020 may further increase the collection and processing of citizen data. Little oversight over this exists in the current legal framework.

This article was first written for the Oxford Analytica Daily Brief, which is the copyright holder.