In November 2014, on the margins of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) meeting in Beijing, Chinese President Xi Jinping and United States President Barack Obama made a joint announcement on climate change, sparking debate around the world about the merits of the deal

Sources

- Hu Shuli, Gong Jing, and Kong Lingyu, “Xie Zhenhua: The climate targets promote reforms compelled by increasingly urgent issues”, Caixin Wang, 1 December 2014.1

- Zhou Ji, Zhang Xiaohua, Fu Sha, Qi Yue, Chen Ji, and Gao Hairan, “A few comments on the China-US joint announcement on climate change”, NCSC website (National Centre for Climate Strategy and International Cooperation of China), 17 November 2014.2

- Tang Xinhua, “US-China cooperation on climate change has become the basis of a new kind of great power relationship”, China.net, 26 June 2015.3

In November 2014, on the margins of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) meeting in Beijing, Chinese President Xi Jinping and United States President Barack Obama made a joint announcement on climate change, sparking debate around the world about the merits of the deal.

The US public reaction was lukewarm4. Some commentators welcomed it as an historic climate change agreement, while others argued that it was a mere restatement of targets that Beijing had already made public. However, the announcement was unanimously welcomed by Chinese media and experts as a fair and satisfying deal from the Chinese point of view.

According to Zhou Ji, Zhang Xiaohua, Fu Sha, Qi Yue, Chen Ji, and Gao Hairan – experts from the National Centre for Climate Strategy and International Cooperation of China (NCSC) – the joint announcement constituted an event “with historical meaning” (具有历史意义, juyou lishi yiyi), marking “irresistible progress towards an ecological civilisation” (生态文明大势所趋, shengtai wenming dashisuoqu). These articles discuss the implications of the deal for future climate negotiations and for US-China relations, as well as the likelihood that each country will meet their targets.

“Key principles”

Chinese commentators are particularly pleased with two key principles in the announcement: that of “common but differentiated responsibilities” (共同但有区别的责任, gongtong dan you qubie de zeren) and that of “respective capabilities” (各自能力, gezi nengli). The NCSC authors say that the acceptance of these principles represents a huge gain for China, since both were points of contention in previous climate change negotiations.

In the Chinese debate, these principles are seen as more important than the quantitative targets. The NCSC experts explain that “the nature and direction of cooperation are more important than data and precise dates. Once the direction of the boat has been determined, it is always possible to speed it up. […] This was not a technical decision, but a decision of political strategy” (联合行动的性质、方向比数值、时间更为重要。航船的方向确认了,是有机会加速达到成功的彼岸的。[…] 它不是一个工程技术的决定,而是一个政治战略的决定, lianhe xingdong de xingzhi, fangxiang bi shuzhi, shijian geng wei zhongyao. Hangchuan de fangxiang queren le, shi you jihui jiasu dadao chenggong de bi’an de. […] Ta bu shi yi ge gongcheng jishu de jueding, er shi yi ge zhengzhi zhanlüe de jueding). The authors say that focusing on strategic direction rather than quantitative targets meant that the deal was more likely to be accepted quickly by both parties and would be more easily implemented.

But the targets are important too. Xie Zhenhua is deputy director of the Development and Reform Commission and responsible for important issues regarding climate change. He tells Caixin Wang that both countries devised their targets independently, so they were not subject to negotiations, although the targets had to meet domestic and international standards. He explains that before the announcement, several Chinese think-tanks came up with estimates on when China would reach peak carbon and CO2 emissions, and therefore when emissions would begin to decline. These studies came to different conclusions: for example, on peak CO2 emissions, estimates varied from 2025 to 2035, with a worst-case scenario of a 2040 peak if the government took no special measures to address the issue. Xie says that the central government created a synthesis of these studies and set the date of 2030 for CO2 emissions to reach their peak.

Some Chinese experts have claimed that China’s commitments are too challenging and will be difficult to fulfil. However, while Xie Zhenhua describes the Chinese objectives as “ambitious” (有雄心的目标, you xiongxin de mubiao), he says they are “attainable with sufficient effort” (经过努力可以做到, jingguo nuli keyi zuodao). Xie says that China’s commitments will be included in the next two five-year plans, to be agreed by National Congress in 2015 and 2020, and so the commitments will be legally binding. However, he notes as important the announcement’s use of the term “approximately” (左右, zuoyou) to qualify the date when peak carbon and CO2 emissions will be reached. Xie says that this signifies that the Chinese government is serious and is not making commitments it cannot keep: “We will make our best possible efforts to attain the goal in advance. But the use of the term ‘approximately’ is realistic and objective” (会争取尽可能早地实现,但“左右”是实实在 在的,是客观的, hui zhengqu jinkeneng zao de shixian, dan “zuoyou” shi shishizaizai de, shi keguan de). Xie also points out that urbanisation, industrialisation, and household consumption will present big challenges, since these three processes will continue to consume huge quantities of energy and thus create more emissions.

The authors say that the US targets are also very ambitious and represent an important step forward from previous US commitments. The NCSC experts say that opposition in US Congress will make it difficult for the government to comply with its stated targets, even if the private sector, R&D groups, and the US states help to meet these goals5.

Domestic pressure

The Caixin Wang journalists who interviewed Xie Zhenhua say that most Chinese media have spoken out against international pressure on China to adopt tough climatechange goals. However, Xie argues that, in fact, domestic pressures carry more weight than international demands. China’s government faces two sources of domestic pressure to address climate change.

The first pressure comes from China’s economic structure, whose imbalances create pressure for “necessary reforms” ( 倒逼改革, daobi gaige). As the central government and the State Council have repeatedly said, environmental reform will necessitate reforms to the entire structure and development model of the Chinese economy. Xie says that China needs to transform its development model on a structural level, because the model is too “expansionist” (粗放, cufang) and relies too heavily on natural resources. This model, Xie says, has allowed China to benefit from high economic growth for several decades, but is not sustainable. Ambitious climate targets will help to put China on the right development path. Xie warns that although this shift is necessary, it will cause Chinese economic growth to decline. He believes, however, that this decline will not be as sharp as it was in similar transitions in developed countries.

The second pressure is the increasing awareness of environmental issues among the Chinese public. Building on his “New Theory of Smog” (雾霾新论, wumai xinlun), Xie says that this awareness is driven by the heavy smog in big Chinese cities, which has made environmental issues hard to ignore. Xie says that this growing public awareness has led to higher quantitative commitments by the government and the acceleration of reforms.

Global negotiations

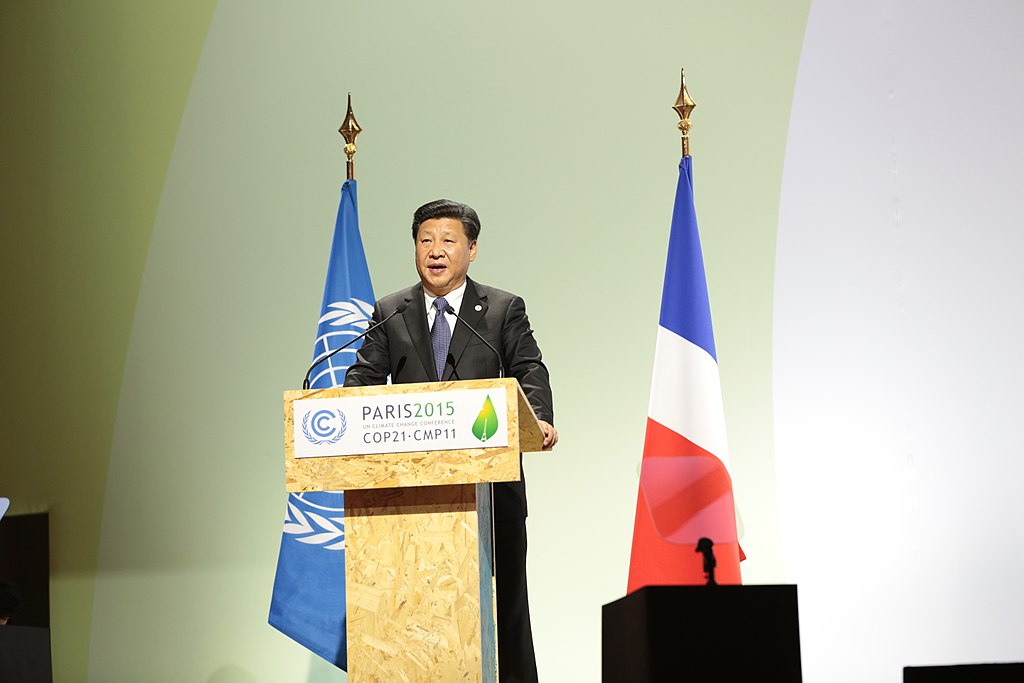

In late 2014, all the commentators cited above predicted that the US-China joint announcement would build momentum around climate negotiations leading up to the Paris round of the United Nations Climate Change Conference in December 2015, and would raise the prospect of serious global commitment to addressing the problem. Xie said that the joint announcement would “play a historic role in promoting a global response to climate change” (对推动全球应对气候变化进程会发挥历史性的作 用, dui tuidong quanqiu yingdui qihou bianhua jincheng hui fahui lishixing de zuoyong).

The announcement included, many months earlier than had been expected, Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs) from China and the US6. At the time, the authors thought that the ambitious targets announced by both countries would give a significant boost to the negotiations to come.

According to Xie, who was interviewed in December 2014, the next key step after the US-China joint announcement would be that month’s United Nations Climate Summit in Lima. The summit, he said, would focus on reaching a preliminary consensus on the global framework and key principles. Xie expected a wide divergence of opinion in Lima, and believed that the outcome would be only a partial draft that simply reflected the position of each country. In the event, the outcome was as he predicted. After the summit, Peru’s Environment Minister Manuel Pulgar-Vidal, who chaired the talks, told reporters: “As a text, it is not perfect, but it includes the positions of the parties7.” Xie predicted that the Paris summit would focus on harmonising these different demands and positions, so that all countries could reach an agreement on climate change.

The authors point out that the joint announcement was all the more important for the upcoming negotiations, since China and the US play a crucial role in the global economy. As all the articles state, the US is the world’s largest developed economy and largest emitter of greenhouse gases, while China is the world’s largest developing economy and second-largest emitter of greenhouse gases. Together, the two countries account for more than 40 percent of global carbon emissions, making their cooperation an absolute necessity.

According to the NCSC experts, the principles of “common but differentiated responsibilities” and “respective capabilities” laid out in the joint announcement will have a major influence on future climate negotiations. They argue that the inclusion of the two provisions will increase developing countries’ confidence in the ability of multilateral institutions to generate consensus and to find a fair solution to climate change. This will boost multilateral governance and ensure widespread participation and joint action.

Xie calls for further democratisation of the international institutions dealing with climate change issues. He says that China’s stance on climate change could play a role in introducing more participative governance to international institutions, especially within the UN system.

US-China relations

Writing at the end of 2014, some of the authors believed that the joint announcement would foster and reinvigorate US-China relations.

The NCSC authors said that US-China cooperation on the climate change issue would not only help in finding solutions to environmental issues, but could push China and the US to adopt a new economic model, create new opportunities for trade, and solve bilateral financial problems.

US-China cooperation, the NCSC authors say, could help modify or even replace the global trade, investment, and financial system. They predict that China’s foreign exchange reserves could be used to invest in clean energy and green infrastructure in the US. This would create a new outlet for Chinese foreign exchange reserves and investment funds, reduce the trade imbalance between the two countries, and boost China’s economic growth.

Tang Xinhua, writing in June 2015, also noted that “the US-China cooperation on climate change has become the basis of a new type of great power relations” (中美气候变化合作成为夯实新型大国关系的基石, ZhongMei qihou bianhua hezuo chengwei hangshi xinxing daguo guanxi de jishi). He writes of past difficulties in US-Chinese relations, stating that the two countries have deep differences on most topics and that public opinion in each country is quite hostile to the other. Tang says that the two countries have found it hard to cooperate in traditional areas, especially security issues. But he argues that they could find common ground on climate change, opening up further areas for cooperation.

In fact, 2015 has seen US-China tensions rise over human rights, cyber attacks, and disputed maritime territories, among other issues. It is still unclear whether Xi Jinping’s visit to the US and the 2015 summit in Paris will ease the tensions and see the two countries coming together around climate change. But Chinese commentators continue to see the US-China deal as a promising stepping-stone for future negotiations.

1: Hu Shuli is the editor-in-chief of Caixin Media and Caixin Weekly. Gong Jing and Kong Lingyu are journalists for Caixin. Xie Zhenhua is deputy director of the Development and Reform Commission. After this article, in April 2015, he was appointed special representative for China for climate change issues.

2: Zhou Ji is deputy director of China’s National Centre for Climate Change Strategy. The other authors are all researchers on climate change issues.

3: Tang Xinhua is a researcher at the Chinese Research Centre on Contemporary International Relations at Tsinghua University.

4: Zachary Keck, “The Faux US-China Climate Deal”, The Diplomat, 12 November 2014, available at http://thediplomat.com/2014/11/the-faux-us-china-climate-deal/.

5: It should be noted here that since these articles were published, President Obama’s Clean Power Plan has been announced (in August 2015), which sets even more ambitious targets for the US regarding climate and energy. For more information, see the Clean Power Plan section of the United States Environmental Protection Agency website: http://www2.epa.gov/cleanpowerplan.

6: Countries across the globe committed to create a new international climate agreement at the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Conference of the Parties (COP21) in Paris in December 2015. In preparation for the conference, countries have agreed to publicly outline what post-2020 climate actions they intend to take under a new international agreement. This commitment is known as their Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs).

7: Brian Clark Howard, “World Moves One Step Closer to Climate Treaty”, National Geographic, 15 December 2014, available at http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/12/141214-unlima- climate-change-conference-global-warming-treaty/.

This article was first written for the China Analytica, which is the copyright holder.