President Xi Jinping’s has moved to address long-term flaws in the fiscal system, and more changes are on the way

President Xi Jinping’s administration has conducted a gradual but sweeping reform of China’s fiscal system. It has rationalised centre-local fiscal dynamics, strengthened fiscal regulation, cracked down on risky local government borrowing and introduced green taxes. It has granted companies significant tax cuts and has pledged even more.

What next

China will maintain a proactive fiscal policy in 2018, with expenditure stable but more focused on the environment and poverty alleviation. Companies will get further tax cuts while green taxes and (especially, in the medium term) a nationwide property tax will take up some of the slack.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Debates about fairness will delay reform of personal income tax.

- Despite institutional reforms, consequential rebalancing of central-local fiscal relationships is unlikely in the medium term.

- Local government debt will grow, but in the less risky form of bonds rather than bank loans to ‘financing vehicles’.

Analysis

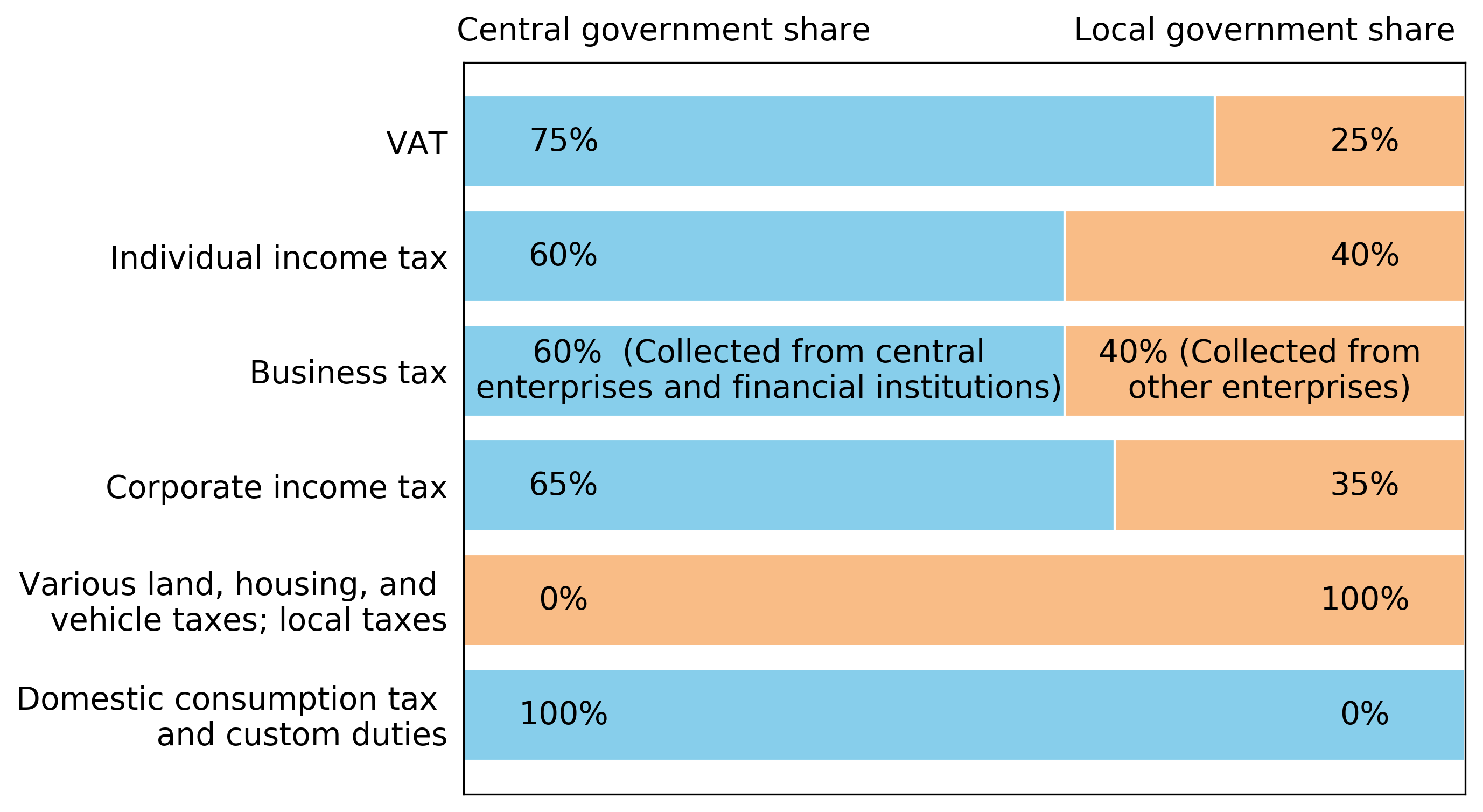

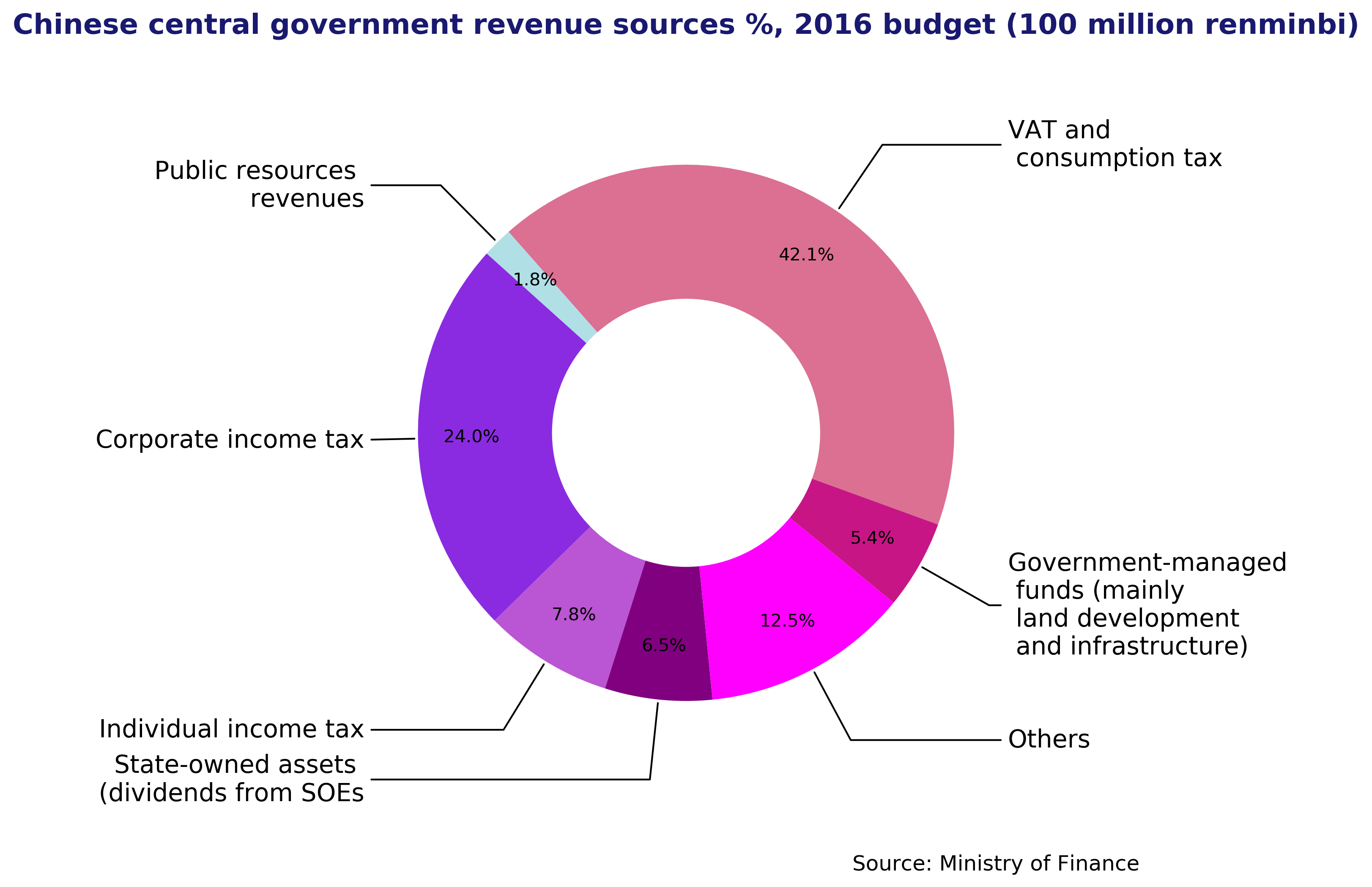

Since an overhaul of the fiscal system in 1994, general fiscal revenues are shared roughly equally between central and local governments.

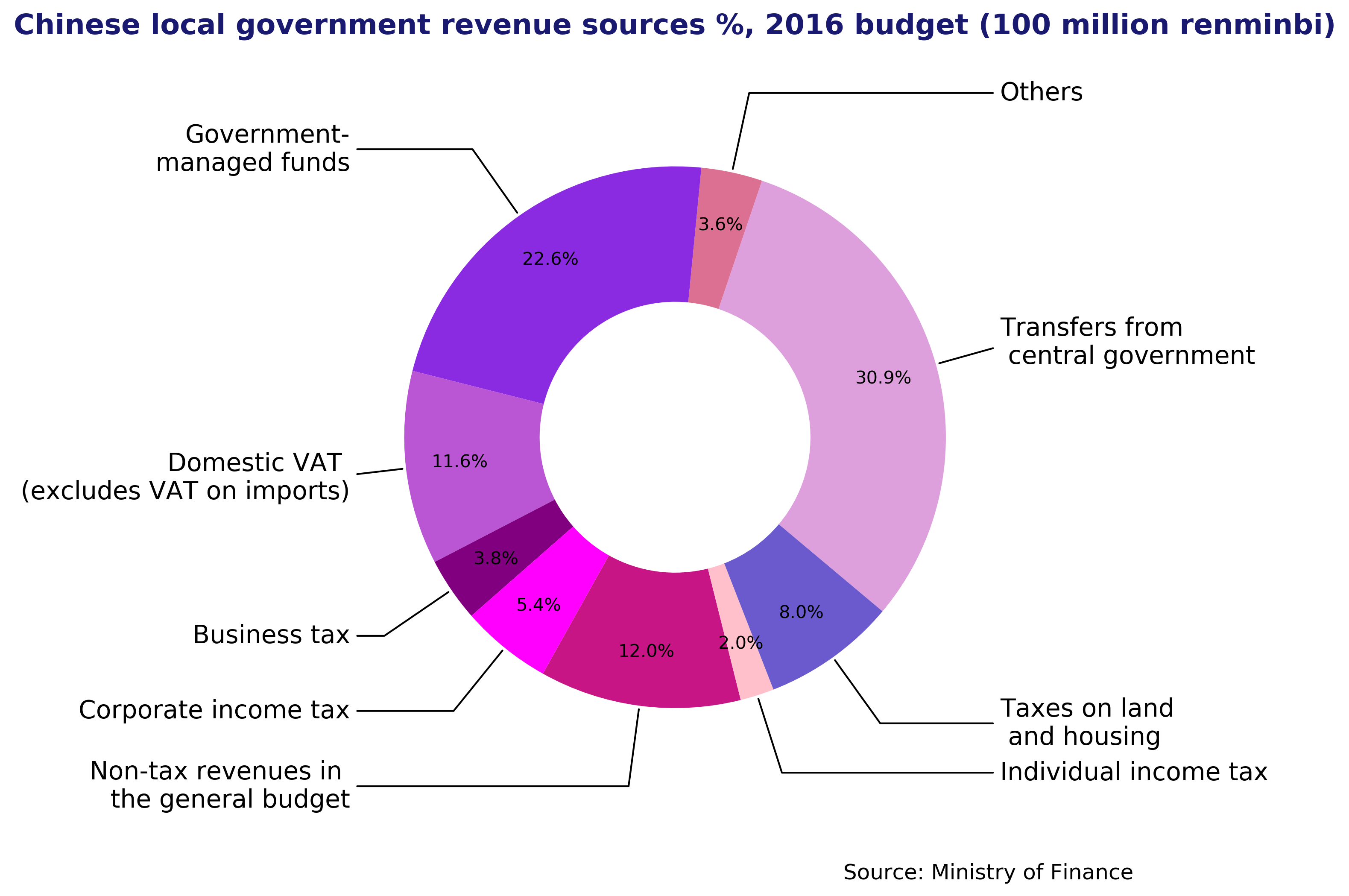

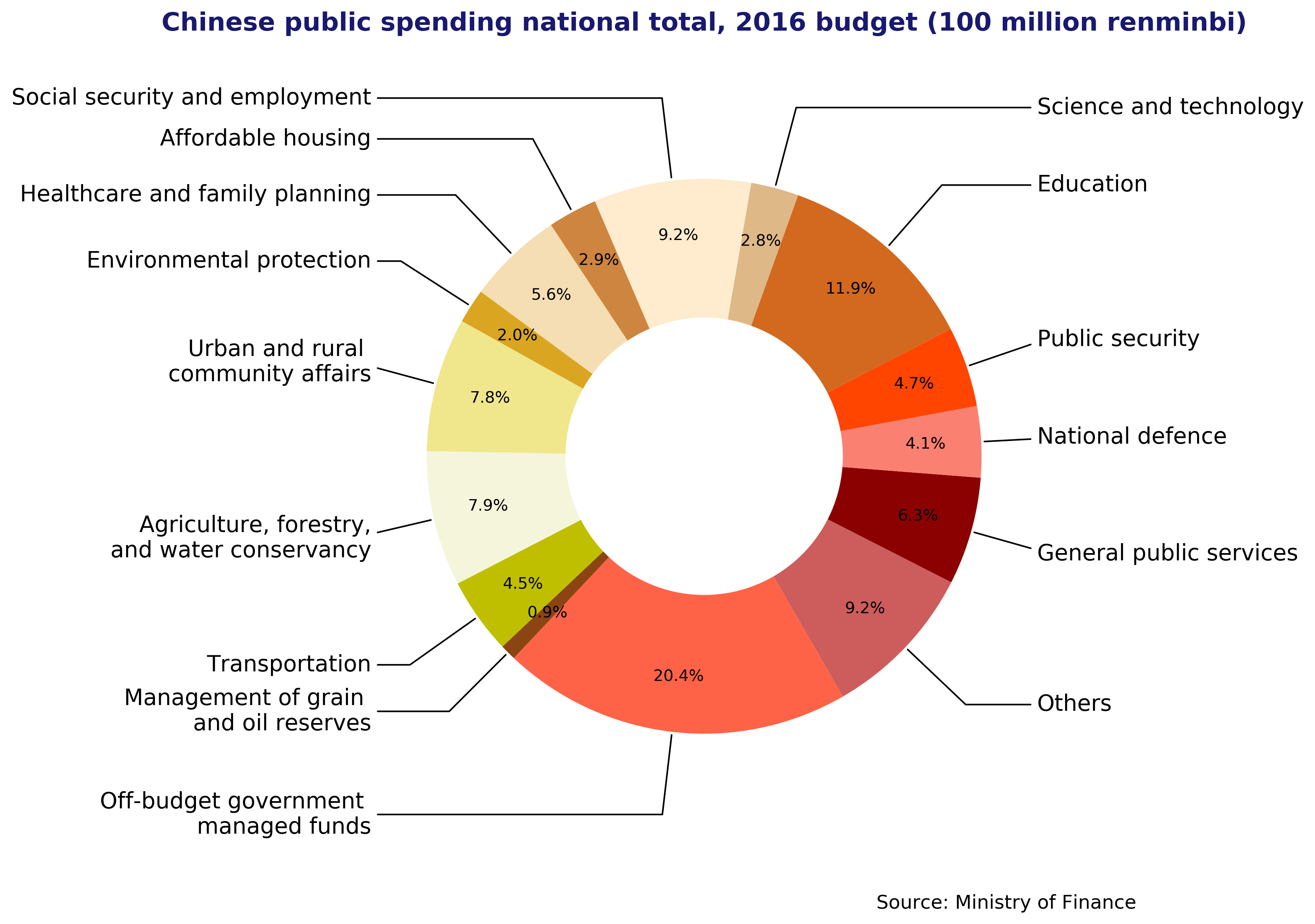

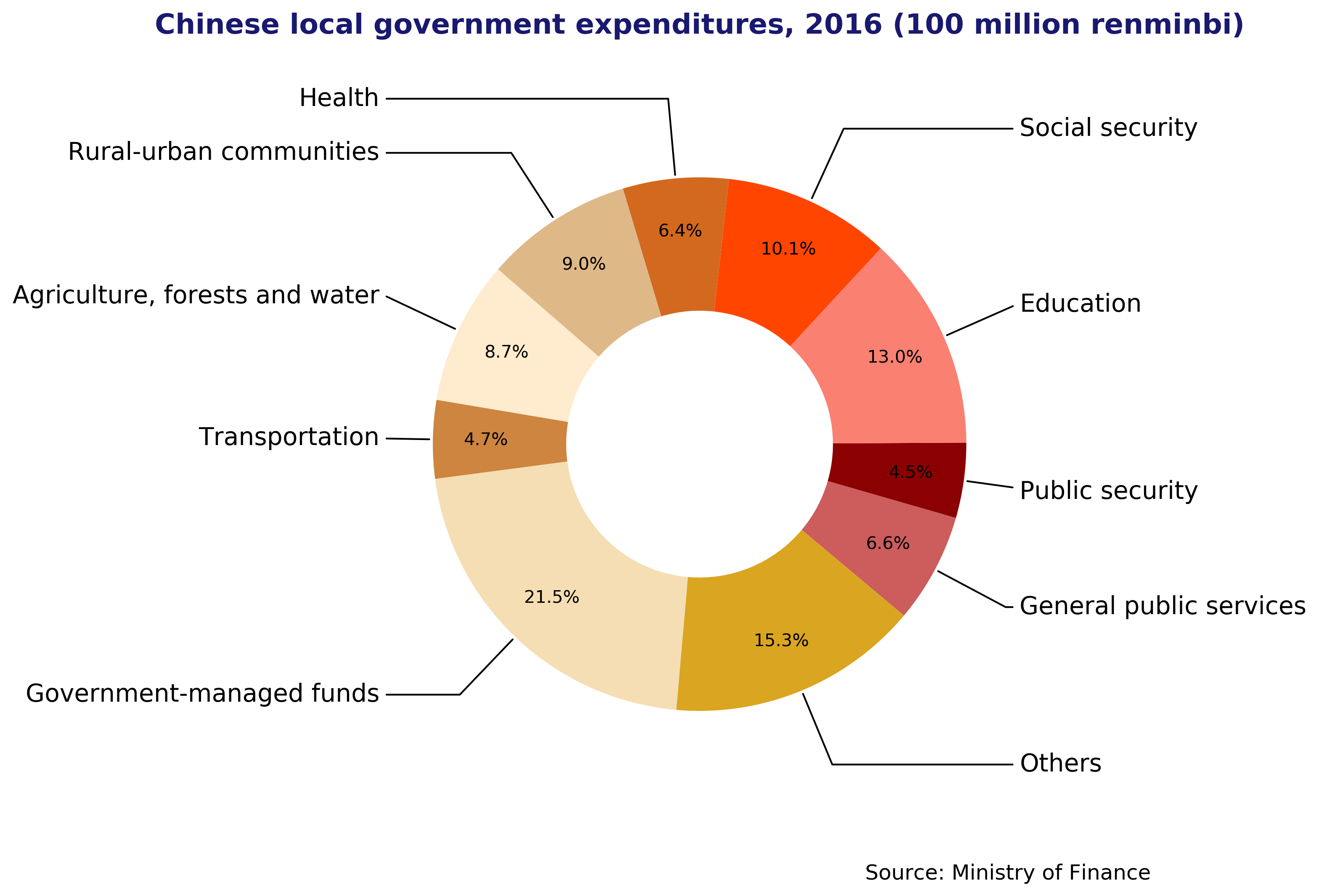

In 2016, local governments received 55% of all general budget fiscal revenues. However, local governments are responsible for more than 80% of fiscal expenditures. Most of the central government’s revenue is redistributed to local governments, but often it is not enough.

Faced with this ‘fiscal starvation’, local governments have found off-budget revenue sources. Most of this comes from fees and fines (12% of revenues) and a category called ‘government-managed funds’ (22%). The latter consists mostly of revenue from the sale of collectively owned land.

However, these ‘off-budget funds’ spend more than they bring in. In 2016, local governments earned 3.7 trillion renminbi from the transfer of land-use rights but spent 3.8 trillion renminbi on compensating dispossessed farmers, improving land quality and building infrastructure.

Land-transfer revenues tend to be used for infrastructure spending in pursuit of GDP targets rather than on social and environmental policies.

Local debt crackdown

Local governments have plugged the gap by borrowing. Their outstanding debt has dramatically risen in the last decade, reaching 16.5 trillion renminbi (2.6 trillion dollars) in 2016 and sparking fears of a financial crisis. Despite the government’s pledge to rein in debt, it has been reluctant to plug local governments' deficits.

Instead, it has tried to reduce the risks associated with informal credit by allowing local governments to issue bonds and banning them from getting loans through ‘local government financing vehicles’ or ‘government investment funds’.

The debt-swap programme that replaces bank debt with official government bonds has reduced the fear of a financial crisis, although local governments' total outstanding debt is still growing.

Reallocating responsibilities

A circular issued by the State Council this month indicates that the division of revenue-raising powers and expenditure responsibilities between central and local government will be rebalanced. The division of expenditure responsibilities will vary across regions according to local economic conditions. The circular also sets national standards for delivery of basic public services and reforms the system of transferring central funds to local governments.

Public spending

Ever since the 2008-09 global financial crisis, China has adopted a proactive fiscal policy to support GDP growth.

In 2014, a 20-year-old budget law was revised to give greater power to the legislature and reorient annual budgeting to a multi-year fiscal framework.

The central government has cracked down on illicit local government borrowing and risky lending practices

In 2016, the public spending deficit reached 3% of GDP for the first time in the history of the People’s Republic. Beijing has pledged to maintain it at this level this year, with more funding going to environmental protection and poverty alleviation (for example, subsidies to poor households, subsidised housing and schooling, and subsidised employment in targeted companies).

Spending priorities

The proportion of social security spending, healthcare and ‘communities management’ (including community services, housing and public facilities) has increased slightly over the last decade. Public security spending, on the other hand, has remained stable over that period.

The proportion of general public services in local government spending has declined, likely reflecting improved efficiency and (relatedly) the effects of Xi’s anti-corruption policies.

Spending on education as a percentage of GDP has also slightly decreased since a peak in 2012. This implies that it is a lower priority for the government, though the government does not admit this and it has still risen in absolute terms.

Tax reforms

Xi’s administration has cut taxes significantly for businesses. It is likely to cut them further.

Corporate income tax

Companies pay corporate income tax on their profits at a standard rate of 25% – slightly above the Asian and European average of around 20-22% (depending on the year).

The range of companies qualifying for preferential rates has expanded, however. Cuts in 2017 alone reduced corporate income tax by 1 trillion renminbi (160 billion dollars), most of it through tax breaks to promote ‘public entrepreneurship and universal innovation’. Corporate income tax revenue rose 11.3% that year nevertheless, due to rises in company profits.

Business tax and VAT

The most significant tax reform in two decades was the replacement of business tax (also called sales tax) with VAT (value added tax). Previously, business tax applied to the service sector and VAT applied to manufacturing. Now VAT applies to both and business tax is being phased out.

The reform was piloted locally in 2012 and expanded nationwide in 2016. The government claims it has reduced tax on businesses by a total of around 2 trillion renminbi so far.

Green taxes

China’s first Green Tax Law took effect on January 1 this year, imposing taxes on air pollution, water pollution, solid wastes and noise.

Property tax

Currently, property is taxed only when bought and sold. The new tax would impose an ongoing charge on owners based on market value.

The aim is to dampen speculation, discourage the holding of empty apartments as speculative investments and bring stable revenues to local governments, which would administer and collect the tax.

A nationwide property tax is a long-awaited reform

According to the finance ministry, legislation will be rolled out in March 2019, but the tax is controversial, and most details are unresolved.

Personal income tax

Although it is only the fourth-largest tax, personal income tax has significant social impact. How to reform it has generated heated debates for years.

The tax is progressive, but advocates of reform argue that rates should be significantly lowered and the income bands widened.

The last reform was in 2011 when legislation raised the monthly exemption threshold to 3,500 renminbi from 2,000 renminbi.

However, amendments to the tax have failed to keep up with income levels. The government wants to make the income tax more comprehensive, basing it on the family unit instead of the individual and allowing deductions for mortgage interest payments, children and supporting elderly relatives.

This article was first written for the Oxford Analytica Daily Brief, which is the copyright holder.