The Xi administration is waging a nationwide campaign to eliminate absolute poverty – and the effort is bearing fruit

Wiping out poverty by 2020 is among the Communist Party’s top policy priorities. President Xi Jinping’s government has granted massive funding to what has become China’s strongest poverty-reduction campaign ever. The population below the poverty line in rural areas has fallen from 99 million in 2012 when Xi took office, to 30 million people by the end of his first term in 2017. Chinese success has attracted praise from international institutions and become a role model for developing countries such as Pakistan in their fight against poverty.

What next

The huge political and financial capital invested in the campaign means that the official goals will probably be largely achieved. That may involve some manipulation of the data, but the impacts will nevertheless be real and dramatic. However, the new approach to poverty relief could also leave significant parts of the population more vulnerable than before.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Stricter monitoring will make poverty relief work more efficient and coincidentally extend Party control over local public institutions.

- Precise targeting of poor households will increase effectiveness, but may leave behind households just barely above the poverty line.

- Businesses will benefit from grants and investments given for undertaking poverty relief and development work.

- Rural populations resettled in urban areas may face greater precarity without farmland to fall back on.

Analysis

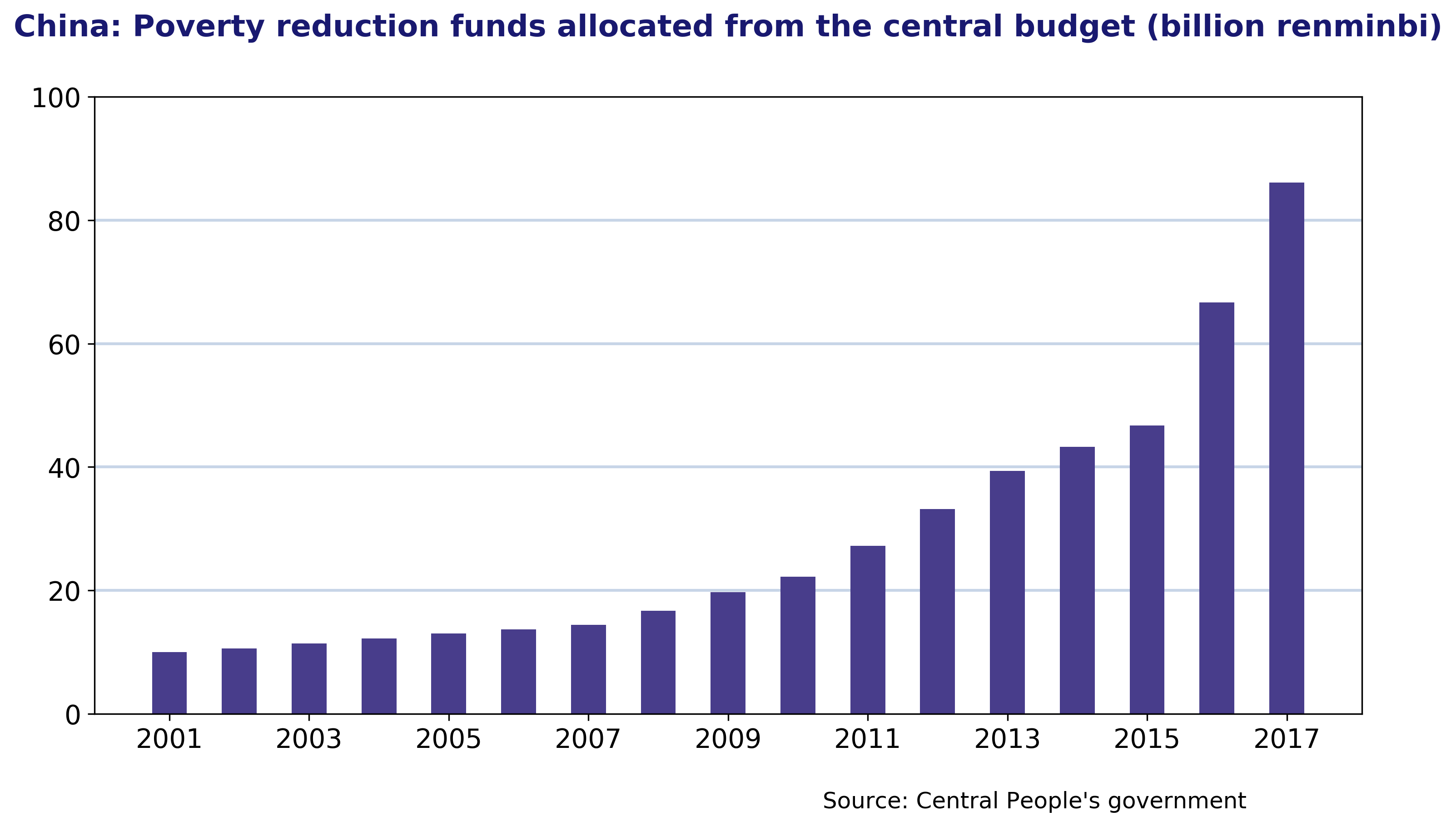

Since taking office, Xi has massively increased the political and financial effort put into combating absolute poverty. Official statistics show poverty reduction funds allocated by the central budget more than doubled since 2012, with a particular jump in 2016 and 2017. Overall, 283 billion renminbi (45 billion dollars) of central government funding has been allocated to poverty reduction during Xi’s first term of office.

Financial institutions – mainly the Agricultural Bank of China, the Agricultural Development Bank of China and the country’s rural credit cooperatives – have also increased their contribution in credit funding. On April 1, China Development Bank, a major policy bank best known for its funding of huge infrastructure projects both in China and overseas, announced plans to lend 400 billion renminbi to support targeted poverty-relief projects this year.

The Xi government also established a poverty alleviation criterion on which officials will be evaluated alongside established criteria such as GDP and social stability.

County governments now have strict targets for how many people must be lifted out of poverty each year between 2016 and 2020. They have less discretion in choosing where to invest poverty alleviation funds, and will be watched closely for misappropriation of funds (see Disobedient local governments)).

Better targeting

The ‘precision poverty alleviation’ approach aims to target poor households more precisely, in line with Xi’s focus on corruption and misallocation of funds.

Poor counties and villages continue to attract funding, as well as a set of 14 special poverty areas identified in 2011. However, the bulk of poverty relief funding is now to be provided based on a family’s total household assets (including house and car), rather than income only, in order to tackle fraud and misallocation.

This improves effectiveness and reduces misallocation of funds, but it gives rise locally to criticisms regarding who gets the subsidies and why. Many households just above the poverty line risk being left behind. The targeted approach has also justified sending hundreds of thousands of local cadres, assisted in some cases by military and paramilitary personnel, to villages to identify poor households and monitor implementation of the campaign. This may have the secondary result of significantly extending the Party’s control over local institutions, including grassroots organisations and village committees.

Market-oriented transition

An important element of the current campaign is its emphasis on the market-oriented transition that Xi’s predecessors initiated. Poverty alleviation programmes are increasingly market-oriented and promote a ‘self-help’ rather than ‘social assistance’ approach.

Instead of unconditional cash transfer programmes, the current projects aim to ‘empower’ residents by improving access to insurance and financial services and subsidising entrepreneurship.

Local elites and businesses are given a central role. For example, in Guizhou, under Xi’s protege Chen Min’er, experiments have been made with ‘industrial poverty relief’. For example, a fund was set up that invests in companies (sometimes very large ones) that supposedly undertake ‘poverty alleviation’ projects. For example, Wanda Group announced in July 2017 that it had invested 1.5 billion renminbi in deprived mountainous areas to support tourism-related poverty alleviation projects.

In some poverty-stricken counties, companies are also given subsidies to hire members of poor households. The government has also allowed companies located in one of the nearly 600 impoverished regions in China to fast-track their stock market launches.

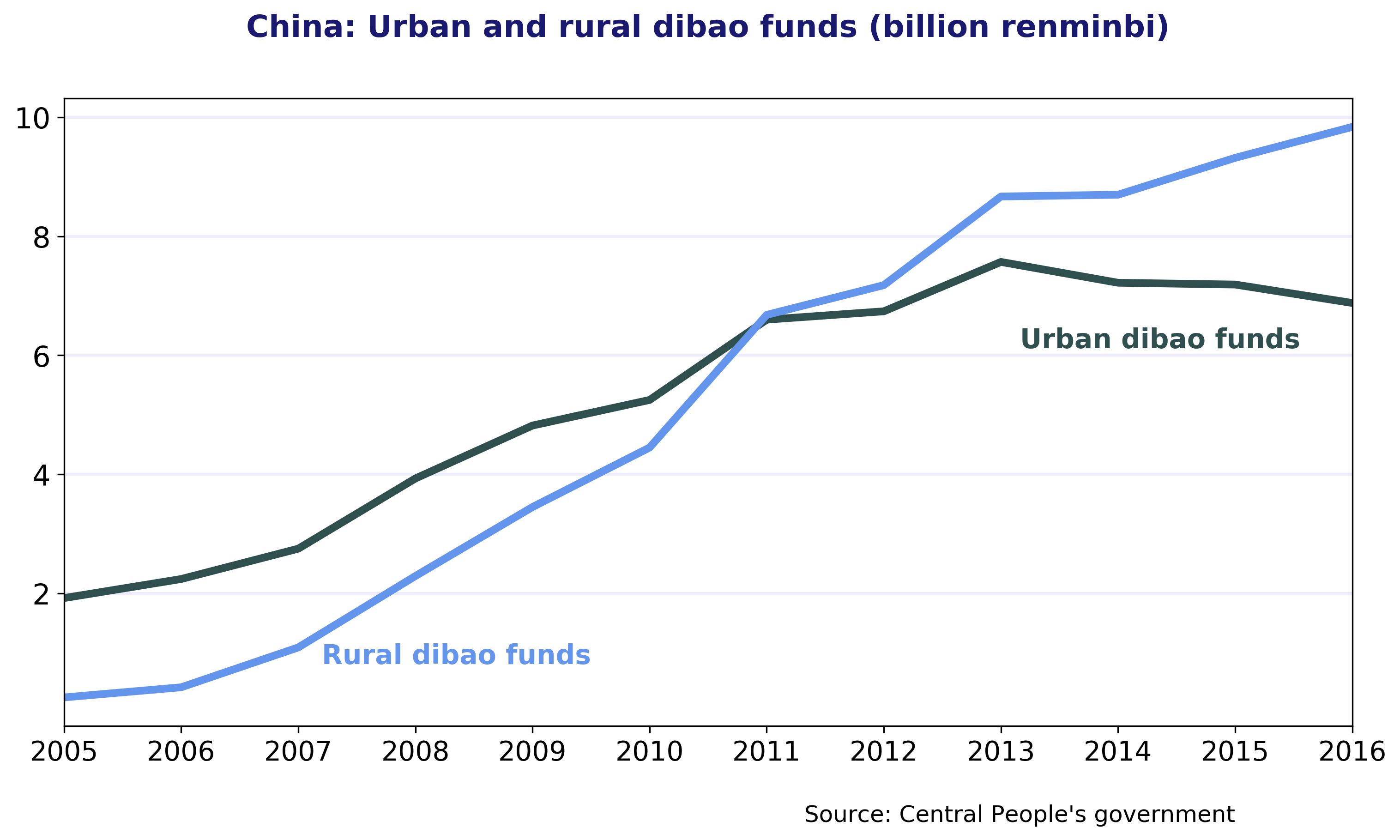

Poverty relief is gradually shifting away from unconditional cash transfer programmes such as the ‘dibao’, a minimum livelihood guarantee for people below the poverty line. Funding for the dibao has begun to stagnate in the countryside and has actually decreased in urban areas. The government wants to expand the coverage of contribution-based insurances and pensions, but these are still far from ensuring a decent standard of living.

Resettlement

Xi’s approach to poverty alleviation involves renewed emphasis on resettlement, a policy launched under Hu Jintao (president 2003-13). It aims to bring rural residents from remote areas to small towns, where they are closer to schools, hospitals and other public facilities, while encouraging urbanisation and agricultural modernisation. Under Xi, the ‘Beautiful Countryside’ programme carries out similar policies, but with a stronger focus on tourism.

The major difference is in the numbers: under the 13th Five-Year Plan period (2016-20), 10.0 million people nationwide will be resettled – four times the previous Five-Year Plan’s 2.4 million target.

The new market-oriented approach to poverty relief consolidates the social role of local elite and businesses

In practice, resettlement programmes do not always result in greater financial security. Local governments use them as a way to appropriate more land for industrial and commercial use (see CHINA: Local government debt risk survives reforms - February 26, 2018). Without their land, farmers lose a crucial safety net and their most valuable asset, increasing the risk of falling back into poverty.

Limits and side-effects

Xi’s poverty alleviation campaign is achieving its goals: around 12 million people were officially lifted out of poverty in 2016, and 10 million in 2017. Though official data should be treated with caution, observations on the ground corroborate claims of dramatic improvements, at least in some areas. The sheer amount of resource allocated means that the goal of reducing the population in absolute poverty to negligible levels by 2020 is likely to be more or less reached.

Better monitoring of local governments and more precise targeting of the poor population will also reduce the corruption and misallocation that characterised past programmes.

10 million people

Population to be resettled by 2020

However, this will not be the end of relative poverty in China. Unless the government significantly improves the scope and coverage of its basic welfare system, significant parts of the population may never achieve middle-class living standards.

This article was first written for the Oxford Analytica Daily Brief, which is the copyright holder.